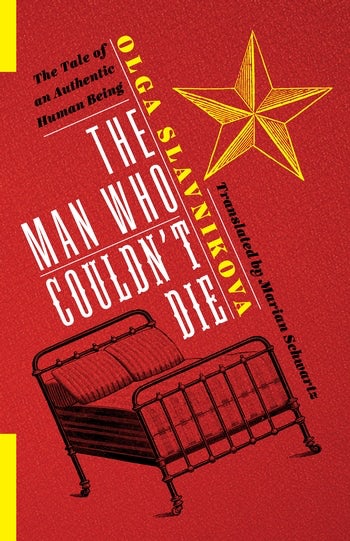

Bibliographic information on The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being Russian Library

Page Length: 272 pages

Publisher: Columbia University Press

Publication Date: January 29, 2019

Author: Olga Slavnikova

Translated by: Marian Schwartz

Contributor: Mark Lipovetsky

ISBN: 9780231185943 (Hardcover), ISBN: 9780231185950 (Paperback), ISBN: 9780231546416 (E-book)

Genre: Literary Fiction, Russian Literary Fiction, Former Soviet Union

Rating: Five stars

About the Author:

Olga Slavnikova was born in 1957 in Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg). She is the author of several award-winning novels, including A Dragonfly Enlarged to the Size of a Dog and 2017, which won the 2006 Russian Booker prize and was translated into English by Marian Schwartz (2010).

About the Translator:

Marian Schwartz translates Russian contemporary and classic fiction, including Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, and is the principal translator of Nina Berberova.

Synopsis of The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being from Publisher’s Page:

“In the chaos of early-1990s Russia, a paralyzed veteran’s wife and stepdaughter conceal the Soviet Union’s collapse from him in order to keep him—and his pension—alive, until it turns out the tough old man has other plans. An instant classic of post-Soviet Russian literature, Olga Slavnikova’s The Man Who Couldn’t Die tells the story of how two women try to prolong a life—and the means and meaning of their own lives—by creating a world that doesn’t change, a Soviet Union that never crumbled.

After her stepfather’s stroke, Marina hangs Brezhnev’s portrait on the wall, edits the Pravda articles read to him, and uses her media connections to cobble together entire newscasts of events that never happened. Meanwhile, her mother, Nina Alexandrovna, can barely navigate the bewildering new world outside, especially in comparison to the blunt reality of her uncommunicative husband. As Marina is caught up in a local election campaign that gets out of hand, Nina discovers that her husband is conspiring as well—to kill himself and put an end to the charade. Masterfully translated by Marian Schwartz, The Man Who Couldn’t Die is a darkly playful vision of the lost Soviet past and the madness of the post-Soviet world that uses Russia’s modern history as a backdrop for an inquiry into larger metaphysical questions.”

Available for pre-order in Hardcover and Paperback at Columbia University Press, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, the E-book version is available for pre-order at Columbia University Press, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Google Play, and will be available soon on Kobo and Apple.

My Review:

I am beginning my review with applause for Marian Schwartz genius translation of The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being. Swartz has established herself as an affluent Russian to English translator beginning in 1977 and has translated more than forty books from Russian to English, including the world acclaimed Russian classic Anna Karenina, one of my favorites. Anyone that speaks more than one language will tell you there is no translation for many words from one language to another, which makes translating a difficult feat. Marian Swartz is a prominent Russian to English translator. To learn more about Swartz, her accomplishments and numerous awards she has received over the years, visit her website provided in the bibliographic section.

The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being is not a casual reading piece of literature for everyone. Just as Anna Karenina would not be the average readers choice for casual reading. As stated in the synopsis, ”The Man Who Couldn’t Die is a darkly playful vision of the lost Soviet past and the madness of the post-Soviet world that uses Russia’s modern history as a backdrop for an inquiry into larger metaphysical questions.” The introspective reader will see a clear resemblance of the political climate of the post-Soviet Union to that of the present-day political climate in the United States, which is perhaps why Swartz chose to translate this particular piece of literature. I found it to be, in many ways, similar to George Orwell’s classic “1984,” another introspective book to read.

Without introspection, some will find The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being slow to grasp and make their way through, but with perseverance, the book begins to mask a time that unmistakably resembles the 2016 presidential campaign. The lights come on, and you are drawn into the story as you read about payoffs, and the promises made but not kept to Russia’s people. And the voter deception, voter fraud at the polls, payoffs, etc.. From campaigning to the counting of the votes that separated the two candidates by nineteen votes with talk of a recount that does not take place, and the protests that follow the election.

“On the other hand, the candidate’s campaign personnel was handing our money to canvassers, and if the money stopped, everyone who hadn’t received their share would vote against Krugal in the elections, “merely out of a sense of outraged justice. The canvassers would get paid and were directed to work slow.” – The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being

During the story, we come to know the elderly disabled veteran and his family, whom all rely on the monthly subsidy the invalid veteran and his family receive to exist upon. The author uses an abundance of metaphysical rhetoric throughout the story. One example is inside time and outside time, which was to keep the time intentionally separated. The inside time, which was the opposite of outside time was the difference between wartime and post-wartime. Inside time was a time some remained living with and could not or would not accept outside time, such as the invalid veteran who wanted to remain on inside time; the inside time was the time he had fought in the war and was severely wounded. Others embraced the outside time and its changes. For many, it was the equivalent to living in two different worlds. Sound familiar? This is just one example of the metaphysical rhetoric the author uses. The characters are descriptive and fit well within the story.

“Marina constructed to “self-contained, illusory worlds” for her decrepit veteran step-father to maintain inside time, which differed from outside time where the war had ended and life was changing, becoming renewed, but the veteran could not know these things.” – The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being

As Benjamin Sutcliffe, from Miami University, said, “The Man Who Couldn’t Die is an overlooked masterpiece of post-Soviet prose by one of contemporary Russia’s most important authors. It reveals how Slavnikova’s descriptions (and Schwartz’s English equivalent) belong alongside those of Vladimir Nabokov, Iurii Olesha, and Nikolai Gogol as truly revolutionary in Russian prose.”

Thank you to Columbia University Press, Marian Swartz and NetGalley for the opportunity to read The Man Who Couldn’t Die: The Tale of an Authentic Human Being

Reblogged this on Finding Courage, Hope, and Faith and commented:

Another interesting read!

LikeLiked by 1 person